110932

论文已发表

注册即可获取德孚的最新动态

IF 收录期刊

- 3.4 Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press)

- 3.2 Clin Epidemiol

- 2.6 Cancer Manag Res

- 2.9 Infect Drug Resist

- 3.7 Clin Interv Aging

- 5.1 Drug Des Dev Ther

- 3.1 Int J Chronic Obstr

- 6.6 Int J Nanomed

- 2.6 Int J Women's Health

- 2.9 Neuropsych Dis Treat

- 2.8 OncoTargets Ther

- 2.0 Patient Prefer Adher

- 2.2 Ther Clin Risk Manag

- 2.5 J Pain Res

- 3.0 Diabet Metab Synd Ob

- 3.2 Psychol Res Behav Ma

- 3.4 Nat Sci Sleep

- 1.8 Pharmgenomics Pers Med

- 2.0 Risk Manag Healthc Policy

- 4.1 J Inflamm Res

- 2.0 Int J Gen Med

- 3.4 J Hepatocell Carcinoma

- 3.0 J Asthma Allergy

- 2.2 Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol

- 2.4 J Multidiscip Healthc

The impact of increased post-progression survival on the cost-effectiveness of interventions in oncology

Authors Retzler J, Davies H, Jenks M, Kiff C, Taylor M

Received 18 October 2018

Accepted for publication 8 March 2019

Published 3 May 2019 Volume 2019:11 Pages 309—324

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S191382

Checked for plagiarism Yes

Review by Single-blind

Peer reviewers approved by Dr Colin Mak

Peer reviewer comments 2

Editor who approved publication: Professor Giorgio Lorenzo Colombo

Purpose: Cost-effectiveness analyses (CEA) of new

technologies typically include “background” costs (eg, all “related” health

care costs other than the specific technology under evaluation) as well as drug

costs. In oncology, these are often expensive. The marginal cost-effectiveness

ratio (ie, the extra costs and QALYs associated with each extra period of

survival) calculates the ratio of background costs to QALYs during

post-progression. With high background costs, the incremental

cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) can become less favorable as survival increases

and the ICER moves closer to the marginal cost-effectiveness ratio, making

cost-effectiveness prohibitive. This study assessed different methods to

determine whether high ICERs are caused by high drug costs, high “background

costs” or a combination of both and how different approaches can alter the

impact of background costs on the ICER where the marginal cost-effectiveness

ratio is close to, or above, the cost-effectiveness threshold.

Methods: The

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence oncology technology

appraisals published or updated between October 2012 and October 2017 were

reviewed. A case study was selected, and the CEA was replicated. Three modeling

approaches were tested on the case study model.

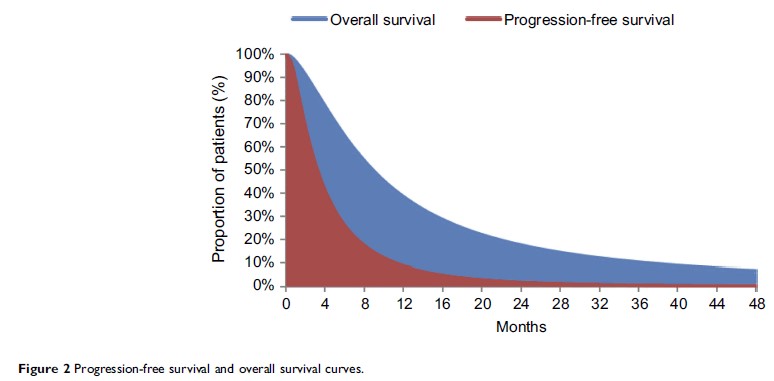

Results: Applying

one-off “transition” costs during post-progression reduced the ongoing

“incremental” costs of survival, which meant that the marginal

cost-effectiveness ratio was substantially reduced and problems associated with

additional survival were less likely to impact the ICER. Similarly, the use of

two methods of additional utility weighting for end-of-life cases meant that

the marginal cost-effectiveness ratio was reduced proportionally, again

lessening the impact of increased survival.

Conclusion: High

ICERs can be caused by factors other than the cost of the drug being assessed.

The economic models should be correct and valid, reflecting the true nature of

marginal survival. Further research is needed to assess how alternative

approaches to the measurement and application of background costs and benefits

may provide an accurate assessment of the incremental benefits of

life-extending oncology drugs. If marginal survival costs are incorrectly

calculated (ie, by summing total post-progressed costs and dividing by the

number of baseline months in that state), then the costs of marginal survival

are likely to be overstated in economic models.

Keywords: cancer,

cost, economics, overall survival, quality of life, modelling